CAR Cell Therapy

Step By Step

-

- Leukapheresis: First, native autologous T cells must be derived from the patient.

- This is similar to stem cell collection before autologous transplantation but involves selecting for CD3 (a T-cell marker) rather than CD34 (a stem cell marker).

- Because T cells normally circulate in our blood, no “mobilizing” medications such as granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) are needed.

- Bridging therapy (optional): treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation may be used to control the underlying malignancy, helping bridge patients through the several-week gap until they can receive autologous CAR-Ts.

- CAR transfer: autologous T cells must be turned into CAR-Ts that contain the CAR of choice.

- Retroviral or lentiviral vectors are typically used for transduction and integration of the CAR into T-cell DNA.

- CAR-T expansion and cryopreservation: Third, these T cells must then be expanded (coaxed to grow) ex vivo and cryopreserved for shipping back to the patient’s bedside

- Release testing and administration: Once the CAR-Ts are back at the patient’s institution, they must be tested. Among other things, release testing involves confirming the sterility of the product as well as the number of viable CAR-Ts. “Out-of-spec” CAR-T products are bags that don’t meet the strict parameters for infusion.

- Lymphodepletion (“LD”): often performed with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, is to make “immunological space” for the incoming CAR-Ts.

- While bridging therapy is optional, lymphodepleting chemotherapy is not.

- Specifically, lymphodepletion alters in vivo cytokine and immune profiles (e.g., by reducing numbers of regulatory T cells and homeostatic cytokine “sinks”) to favor the expansion of incoming CAR-Ts.

- Monitoring for CRS: #todo

Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS):

- CRS is generally thought to be driven by pro-inflammatory cytokines (in particular, IL-6) released by monocyte-lineage cells, rather than by the CAR-T cells themselves.

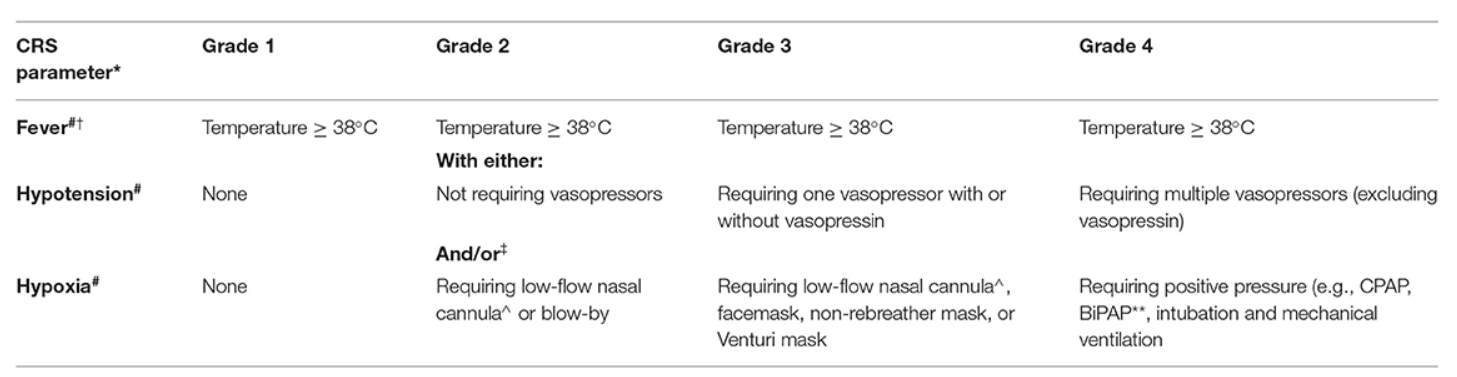

- CRS typically presents with fevers; in more severe cases hypotension or hypoxia may develop.

- The mainstay of CRS treatment is tocilizumab (“toci”), an IL-6 receptor antagonist and corticosteroids.

- While biomarker patterns (e.g., a rising ferritin or CRP) can help suggest CRS, CRS remains a clinical diagnosis.

- CRS can mimic bacterial sepsis, thus neutropenic fevers in a CAR-T therapy recipient must be treated w/ empiric antibiotics even if CRS is more strongly suspected.

- MSK CRS Protocol: [[MSK CRS Protocol.pdf]]

Other Adverse Effects:

- Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS):

-

Thought to be driven by pro-inflammatory cytokines entering the central nervous system (CNS) even if the CAR-Ts themselves do not.

-

ICANS-related encephalopathy often presents with subtle word-finding difficulties but can progress to cerebral edema or seizures.

-

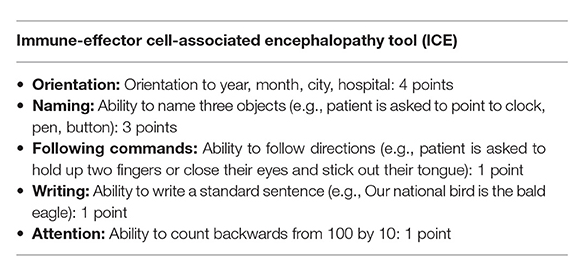

The ICE assessment is generally used to evaluate patients for neurological deficits following CAR-T therapy. Corticosteroids are the mainstay of ICANS treatment, and sometimes levetiracetam is used for prophylaxis.

-

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH):

- Similar in presentation to CRS, but more likely to involve hyperferritinemia, coagulopathy, and transaminitis.

- Anakinra (an IL-1 antagonist) is often used preferentially here, along with high-dose corticosteroids.

- Cytopenias:

- Low blood counts and frequent transfusions are very common in the weeks following CAR-T therapy for many reasons: a heavily pre-treated bone marrow, underlying disease, lymphodepleting chemotherapy, CRS occurring within the marrow, etc.

- Growth factors, in particular G-CSF, are often avoided during the first one to two weeks after CAR-T administration to avoid the theoretical risk of exacerbating CRS.

- Infections: CAR-T recipients are highly susceptible to infections, in part due to low counts as explained previously.

- Additionally, on-target hypogammaglobulinemia (both with CD19-directed and BCMA-directed products) or the use of tocilizumab and corticosteroids can predispose patients to infections.

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis (including antifungal agents for high-risk patients) is often used for several months following CAR-T therapy, and some may also require IVIG.

- Other Organ Toxicities

- Cardiac (tachycardia, arrhythmias, heart block, heart failure)

- Respiratory (tachypnea, pleural effusion, pulmonary edema)

- Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea)

- Hepatic (ALT/AST/Bili elevations)

- Renal (AKI, decreased urine output)

- Dermatologic (rash)

- Hematologic (Coagulopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation)

References:

Created at: periodic/daily/August/2023-08-01-Tuesday